A Matter Of Time.

A couple of weeks ago when I met friend and fellow blogger Ann Koplow one of the things we talked about was the art of blogging, a subject I meant to bring up in my first post about our meeting, but I got distracted, which often happens to me, especially when I get into an engaging conversation, as Ann and I did, although I can also get distracted when I’m by myself, and I was going to share an example of that but now I’ve forgotten what it was because one of the dogs started barking in the other room and I had to go see what was going on and while I was doing that I thought I’d get some water and the next thing I knew I was outside in the driveway surrounded by parts from our car’s engine, but that’s another story.

Anyway Ann asked me an interesting question: “How long does it take you to write a blog post?” And I was so surprised that I said, “About a day,” which seemed like an honest answer at the time and which may be correct, but I’ve never really thought about it and feel guilty about not giving the question more thought before I answered, or at least not saying, “I don’t know. I’ve never thought about it.” I could have said that everything I write has taken me my whole life, and it’s true that every idea is the summation of a lifetime of experience, but it’s just as true that all writing is selective—everything’s edited even before the actual editing—and there are things I could have written earlier in my life if I’d just gotten the idea. Some posts take hours to write and even though I’m an obsessive reviser don’t have a lot of changes. Some take months or years and end up being something very different from my original idea. Before I started actually writing this I wanted to fit in a joke about “How long is a piece of string?” but that got cut.

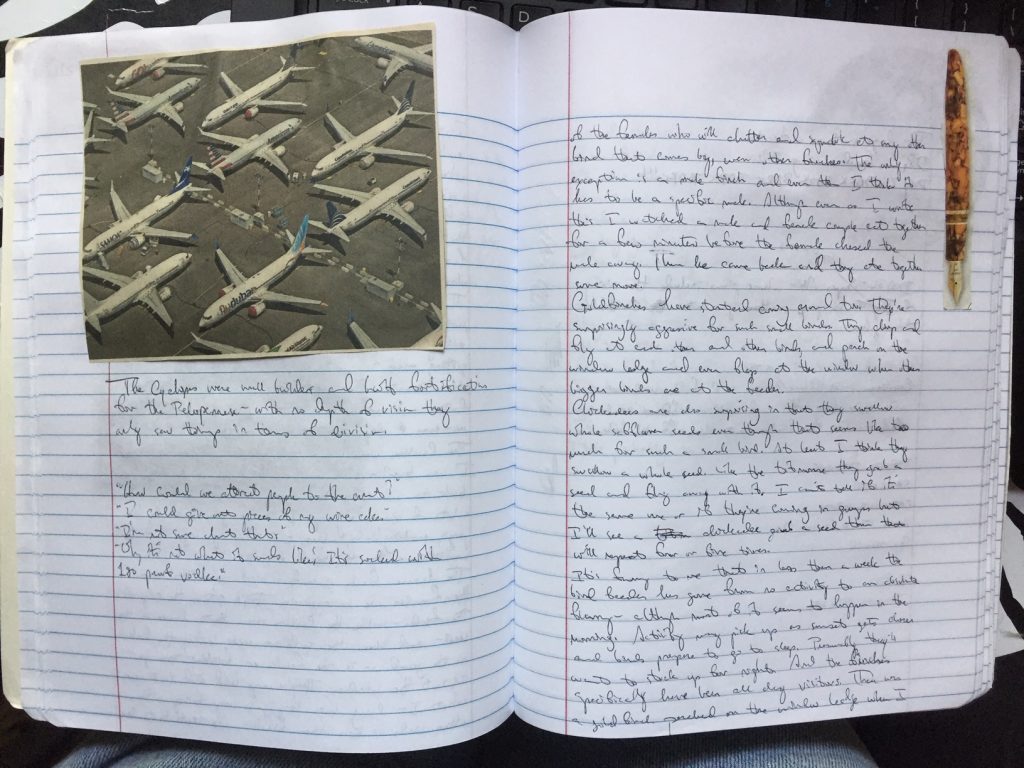

Ann writes a blog post every day which is impressive but I could also understand what she meant when she said it was a meditative process for her. I write almost every day and try to write every day, even if it’s just a few minutes of jotting thoughts down in one of my journals, because I feel better when I do.

Something else I think most writers can relate to is I’m always thinking about writing even when I’m not engaged in the act. Probably every writer has had the experience of suddenly coming to in their backyard surrounded by car parts and thinking, “There’s a story in this.”

Something else I think most writers can relate to is I’m always thinking about writing even when I’m not engaged in the act. Probably every writer has had the experience of suddenly coming to in their backyard surrounded by car parts and thinking, “There’s a story in this.”

There’s no single answer to Ann’s question and that’s what makes it so important and useful for consideration, so I thought I’d throw it out there. How long does it take you to write a blog post?