Just for fun here’s my latest paper for the Jewish Humor class I’m taking. It should come as no surprise that I lean more strongly in favor of Mel Brooks, but I do think Eddie Cantor was a very funny guy who just made some awful choices.

Western Transformations

by Christopher Waldrop

The appeal of the American West is as a place of both freedom and opportunity for all people regardless of background, of wide-open spaces where hostile conditions mean survival depends on strength and wit, and where an individual can be, willingly or unwillingly, transformed. This makes it a place of special appeal to people seeking to escape persecution or simply looking for better lives. In Jews Of The American West Moses Rischin writes,

For Jews, the loose-jointed cosmopolitan socirty of the West offered not only economic opportunity but social acceptance and political place markedly in advance of other regions of the country. (Rischin, 28)

The West was also a place where an individual could remake him or herself. As Andrea Most says in Making Americans: Jews And The Broadway Musical,

Like the streets of New York City, the mythical nineteenth-century American West promised anonymity and freedom from conventional social hierarchies. The newcomer in a Wild West town was like an immigrant: he started fresh. No one knew who he was or where he came from, and so his chances of success depended on how well he inhabited the role he chose. (Most, 42)

Perhaps this is why the films Whoopee and Blazing Saddles, produced forty-four years apart, both deal with race and with transformation, albeit in very different ways.

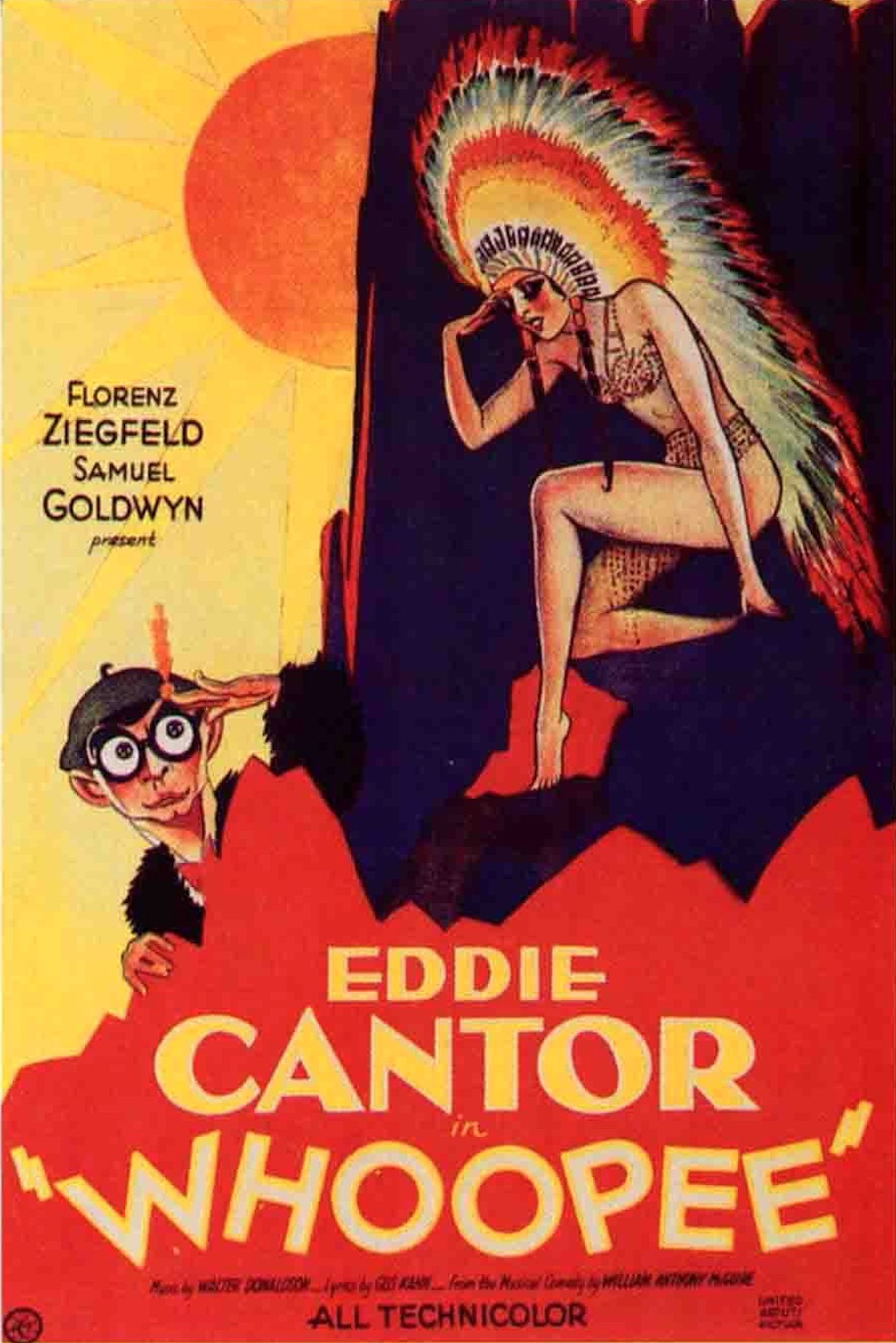

The plot of Whoopee, starring Eddie Cantor and based on a stage play produced by Florenz Ziegfeld, is fairly straightforward. The film opens with a large musical number, and it was, in fact, the big screen debut of choreographer Busby Berkeley. The number announces and celebrates the wedding day of Sheriff Bob Wells and the rancher’s daughter Sally Morgan.

However Sally loves Wanenis, but can’t marry him because Wanenis is part Native American. As he explains to the hypochondriac farmhand Henry Williams, played by Cantor, “my great-grandfather married a white girl”, but has also become assimilated into white culture. He says, “Why, I’ve gone to your schools,” which causes Henry to exclaim, “An Indian in a Hebrew school!”

Unwilling to marry the sheriff Sally asks Henry to take her away secretly under the pretense that Bob doesn’t want to cowboys to get “too boisterous” and that they plan to marry in another location when she really plans to escape. She leaves a note for her father that she’s eloped with Henry. A chase ensues with Bob swearing to hang Henry. Henry’s nurse, Miss Custer, who is in love with him, also plans to kill him for his betrayal. When the car Henry and Sally are traveling in runs out of gas on a narrow mountain pass Henry suddenly demonstrates remarkable resourcefulness, if not courage, as he uses a gun Sally has given him to make a wealthy family give them some gasoline. Now pursued by both the sheriff and his men and the wealthy family (whose name is later revealed to be Underwood, giving Cantor a chance to make a joke about typewriters), Henry and Sally stop at a ranchhouse where Henry is hired as a cook, in spite of not knowing how to cook. When the owner asks him to make waffles Henry pours ketchup, Epsom salts, and flour into a bowl, singing “makin’ waffles” to the tune of “Makin’ Whoopee”, which he’d performed earlier. Miss Custer, dressed as a cowboy with a fake moustache, confronts Henry. She’s closely followed by Mr. Underwood who doesn’t recognize Henry and the two exchange surgery stories. When Sheriff Bob and his men arrive Henry hides in a stove which explodes, putting him in blackface. Sally calls this disguise “perfect”, and Henry fools Sheriff Bob and the others into thinking he’s someone else by singing and dancing. It’s difficult to bear the strain on credibility here, even for a musical.

When Henry’s blackface is wiped away and his true identity is revealed he and Sally escape again, only to be kidnapped by Native Americans who take them to their camp where Sally is reunited with Wanenis and they profess their love for each other. Henry, meanwhile, becomes part of the tribe, calling himself “Chief Izzy Horowitz”. The treatment of Native Americans is as problematic as the blackface, as they all speak in broken English and grunts, and insist that Henry smoke a pipe. There is also an elaborate musical number of Native Americans parading and dancing.

The arrival of Miss Custer again puts Henry’s life in danger, as does the arrival of Sheriff Bob and his men. At this point the chief of the tribe reveals that Wanenis was the child of white settlers. Wanenis is allowed to marry Sally, Henry, with some trepidation, agrees to marry Miss Custer, and everyone rides off on horseback, with the flivver Henry and Sally drove left to its own fate.

Unlike Whoopee which uses racism as a plot element without criticizing it Blazing Saddles, directed by Mel Brooks and with a screenplay with contributions by Richard Pryor, has a plot largely driven by racism as well as criticizing it. In conversation with Mike Sacks, Brooks attributes this to reading Gogol, saying that the Russian writer’s influence prompted him to write “about subjects such as racism for blacks, racism for Mexicans, the indignity suffered by Asian railroad workers.” (Sacks, 442). In the film’s opening an Asian railroad worker collapses in the heat and is docked half a day’s pay “for sleepin’ on the job”. The white overseers frequently use racial slurs and try to get the African American workers to sing. After Bart, played by Cleavon Little, and another worker barely escape drowning in quicksand Bart assaults the overseer Taggart and is sentenced to be hanged. He’s saved when the governor’s assistant Hedley Lamarr sees an opportunity. The railroad will have to be redirected through the town of Rock Ridge, and by appointing Bart the sheriff he can easily drive out the people and seize the land. Bart is threatened by the townspeople on arrival but tricks them into letting him go by holding a gun to his own head. Although Bart was clearly liked and respected by his fellow railroad workers, leading them in a performance of Cole Porter’s “I Get A Kick Out Of You”, this is the first time we see his resourcefulness, in much the same way that Henry in Whoopee only demonstrates wit under pressure when he robs the Underwoods.

Bart befriends Jim, an alcoholic gunslinger known as “The Waco Kid”, and shares the story of how his family came west in a wagon train. Because of their race his family was forced to stay far behind the main group, and the settlers are surrounded by “the entire Apache nation” and circle their wagons Bart and his family drive their own wagon in a circle. They then meet the Apache leader, played by Mel Brooks. Unlike the Native Americans in Whoopee Brooks speaks in Yiddish. When another starts to attack the family Brooks says, Zeit nisht meshugge (“Don’t act crazy” and tells Bart’s family to go abee gezint (“As long as we’re healthy”). While it’s not clear why he releases Bart’s family he does turn to another and ask in Yiddish, “Have you ever seen such a thing?” before adding in English, “They darker than us!” However these Native Americans are not a joke or the “noble savage”, and by having them speak Yiddish Brooks ties the long Jewish history of exile to the much more recent Native American history of forced displacement and exile.

When Lamarr threatens the town by sending the brute Mongo, who punches a horse (a nod to Sid Caesar who once did the same) and crushes saloon patrons behind a piano (music’s charms don’t always soothe the savage breast) Bart subdues him with an exploding candygram and wins over both the townspeople and Mongo. Lamarr’s attempt to undermine Bart by having the “Teutonic titwillow” Lili Von Shtupp seduce him also backfires. His other plans having failed Lamarr plans an all-out attack on Rock Ridge with every Western villain he can find, including Methodists.

There is no blackface in Blazing Saddles, since Bart’s intelligence and charm do the work of mocking racism, but when Bart and Jim sneak into Lamarr’s camp in Klan robes it’s one of Bart’s hands that gives him away. Jim tries to save the situation by calling him “Rhett”, but Bart unmasked, says, “And now for my next impression…Jesse Owens!” He then convinces the townspeople and the railroad workers to join together in racial harmony to build a duplicate Rock Ridge which they use as a trap to capture Lamarr’s gang.

The big fight scene seems at first like a parody of other westerns, with a shot of Bart and Jim accidentally punching each other in the chaos, but it quickly spills out into the Paramount lot and into another film studio where Dom DeLuise is directing a Busby Berkeley-style musical, albeit with all-male dancers in tuxedoes. This recalls an early scene in Whoopee where several of the men are dressed in tuxedoes for Sally’s wedding. The fight continues into the Paramount commissary and then into the street. Bart chases Lamarr and shoots him in front of Grauman’s Chinese Theater where Blazing Saddles is playing. Bart and Jim then go in to watch the end of the film. Shooting the bad guy isn’t enough; there must be an epilogue in which Bart, back in Rock Ridge, tells the townspeople he’s leaving to fight injustice. The townspeople respond with a unanimous “BULLSHIT!” It’s funny, but also a stern reminder that racism cannot be solved by a single person. Bart and Jim then ride out to where a Cadillac waits to drive them off into the sunset. While Bart himself is not transformed, but rather, like Henry Williams, a character who draws on skills he always possessed, the people of Rock Ridge are left kinder and more tolerant, and the former railroad workers are given land on which to build homes. There is uncertainty and ambiguity in this ending, but, ultimately, I find the conclusion of Blazing Saddles much more satisfying than the fairy tale ending of Whoopee. Perhaps this is an unfair comparison, though, as the experience of watching any film must ultimately leave the viewer transformed.

Works Cited

Rischin, Moses and Livingston, John, Jews of the American West, Detroit : Wayne State University Press, 1991

Most, Andrea. Making Americans: Jews and the Broadway Musical, Harvard University Press, 2004

Sacks, Mike, Poking a Dead Frog: Conversations with Today’s Top Comedy Writers, New York, Penguin Books, 2014

Whoopee, 1930 film directed by Thornton Freeland

Blazing Saddles, 1974 film directed by Mel Brooks

One of my favorite parts in “Blazing Saddles” (and I have a kashmillion favorite part of that movie) is when the townspeople are thinking about working together with all races for their mutual benefit, and one of the town leaders says, “Alright! We’ll take the (racial slur) and the (racial slur), but WE DON’T WANT THE IRISH!” before he relents and accepts everybody. That says to me that old prejudices die hard but they can be transformed. And I think every Jewish person, when they saw “Blazing Saddles” in 1974 in a movie theater, loved the “private joke” of Mel Brooks as a Native American speaking Yiddish. That’s probably a gross overgeneralization, but every time I saw it in the theater, I heard the scattered outbursts of laughter as announcements of my tribe. Also, I was aware of a theory that Native Americans were one of the “lost tribes” of Israel, which added to the joke. Here’s a link discussing that theory, in case you ever want to write a paper as excellent as this one about that: https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/native-americans-jews-the-lost-tribes-episode/

That’s fascinating–I think I’d heard the theory that Native Americans were one of the lost tribes of Israel–in fact I now remember I read a science fiction novel called The Aquiliad in my youth that, weirdly and with tongue planted firmly in cheek, placed the lost tribe in the Pacific Northwest. They’d settled there because it was a good place to get smoked salmon.

Mel Brooks as a Native American speaking Yiddish is, I think, one of many examples of Brooks’s films really having much greater intellectual depth than he’s usually given credit for.