Wish Upon A Star.

Have you ever made a wish on a star? Traditionally wishes are made on the first star to appear in the evening. Maybe that’s because the first visible star is the brightest and therefore able to shine through the sun’s lingering radiance, and was there long before you could see it, although the brightest stars aren’t necessarily the closest stars, and the more distant stars may not even be around anymore. Maybe stars are such lousy wish-granters because we’re wasting our wishes on the ghostly light of stars that burned out long ago. And can wishes move faster than the speed of light? If not and if you get lucky enough to make a wish on Proxima Centauri it’s going to be more than four years before your wish gets there and just as long before it gets back. I don’t know about anyone else but my priorities when I was seventeen were very different from when I was nine.

Maybe I’m overthinking this.

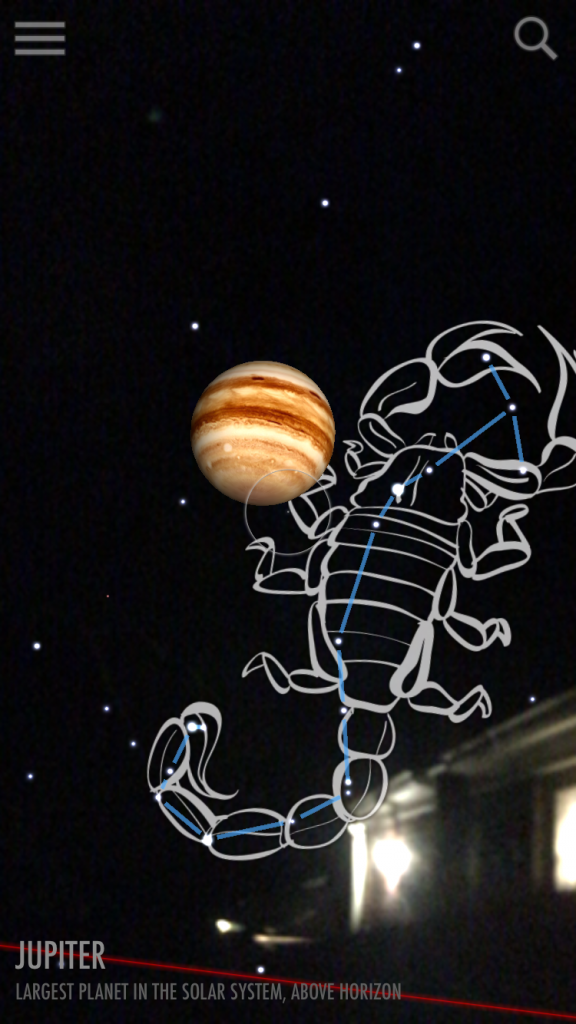

Sunday morning, after Daylight Savings Time ended and all the clocks fell back an hour, I got up early because my wife was going somewhere and I helped her load stuff into the car, take the dogs out, and whatever else needed to be done. I don’t remember exactly because my brain was still hanging out an hour back, but after she left and before I went back inside I looked to the south and there was a single star, bright enough to still be visible in the approaching dawn. And it was definitely a star, not a planet.

It was the star Alphard, the brightest star in Hydra, the constellation of the snake. The constellation is Greek, but the star’s name is Arabic for “the solitary one”, and it’s one of the stars on the Brazilian flag, representing the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, and it’s on that state’s flag.

I can’t say I knew all of that while I was standing out in the backyard. Some of it I had to look up, including the fact that Alphard is larger and brighter than Earth’s sun, although cooler, and about one hundred and seventy-seven light years away, which makes it a relatively close cosmic neighbor, although still farther than you’d want to go for help if you locked yourself out of your house.

What I did know, standing out there in my bathrobe, is that the weather has gotten colder as we’ve moved into November, as the Earth’s orbit has taken it to closer to the sun, making the northern hemisphere’s nights longer, and that got me thinking about time. The ways we measure time–hours, minutes, even days–are arbitrary. Some cultures begin days at sunup, others begin at sundown, and in either case the sky never goes from completely light to complete dark in one swell foop. Time itself, though, is more of a mystery. Ever since Einstein we’ve known time and space are one thing, part of a continuum, and that matter affects space a time–an affect we can see in a picture of an eclipse, the sun’s gravity bending the light of other stars around it. The greater an object’s mass the slower time moves around it, and the faster an object moves the greater its mass, which is a thought I’ve been turning over in my head since I was seventeen. Is movement simply a way of marking time or are time and movement fundamentally linked? And does this have anything to do with temperature? Movement generates heat, whether it’s the energy released by stars knocking hydrogen atoms into each other or heat produced by the movement of molecules, movement that only stops at absolute zero. If you could stop all time around you but keep moving, like in a science fiction story, would you freeze because all the matter around you was no longer generating heat?

I shivered in my bathrobe. I’d lost track of how long I’d been standing there in the backyard staring at a solitary star as it dimmed in the growing light of a much closer star, so I walked to the door and wished I hadn’t locked myself out of the house.