July 11, 2014

Here’s how it was supposed to happen:

The doctor would call my wife and I into his office, which I imagined would be a wood-paneled room lined with books. He would rest his elbows on his desk and fold his hands, and, quietly and soberly, say, “Mr. Waldrop, Im afraid you have cancer.”

And I would say, Id like a second opinion.

At this point I expect hed start looking through a list and saying something about referrals, and I’d have to stop him and say, “Doc, you’re supposed to say, ‘And you need a haircut.'” And I would have to explain to him who Henny Youngman is, because they don’t teach the important things in medical school.

Here’s how it did happen:

I’d been in for an appointment about an ongoing pain in my leg. This had lasted a couple of months, and I was tired of it waking me up at night. While he was telling me to turn my head and cough my doctor noticed some other things that concerned him, so he ordered some tests, including an ultrasound and a CT scan. Some other doctors might not have taken the time or been concerned, but he didn’t see any need for delay. My wife and I were on our way home from those tests when the doctor called my wife’s cell phone. In fact we were two blocks away.

“Chris needs to be taken to the emergency room right away. He has a blood clot in his leg. Also he has testicular cancer.”

I know that if he could have had the sober wood-paneled office meeting he would have, but while cancer is slow blood clots have a tendency to cause sudden death. And my diagnosis would play a part in my treatment over the longest three days of my life.

So we turned around and went to the emergency room, where we managed to find a couple of chairs together in a corner. This was a Tuesday, and I would later be told that emergency rooms are busiest early in the week, maybe because it takes sick people a while to recover from their hangovers. After about twenty minutes I was called back by a nurse. We sat on opposite sides of a desk and I was subjected to a routine interrogation. It included taking my blood pressure, and being asked the following questions:

”Are you allergic to anything?”

“No.”

“Are you taking any prescription medications or drugs?”

“No.”

“Do you have any religious or cultural sensitivities we should be aware of?”

“No.”

I made the mistake of thinking this was progress. Instead I was sent back to the waiting room where, after five minutes, I was prepared to offer my spot in line, or at least cash, to anyone who could figure out how to change the television to any show not set in a hospital. Ten minutes later I was called back by another nurse. Progress! She took my blood pressure and asked me some strangely familiar questions.

“Are you allergic to anything?”

“No.”

“Are you taking any prescription medications or drugs?”

“No.”

“Do you have any religious or cultural sensitivities we should be aware of?”

“No.”

And it was back to the waiting room where a kid with green-tinted hair and bright green skin sat listening to a pair of bright red headphones. His problem seemed more urgent than mine, but he was still waiting when I was called back again. This time I was led to an oversized closet with a bed. I was given a gown to change into and a pair of socks with sticky pads on the feet. A few minutes later a nurse came in to take my blood pressure and ask a surprising series of questions.

“Are you allergic to anything?”

“Belgians.”

“Are you taking any prescription medications or drugs?”

“Just baby aspirin and PCP.”

“Do you have any religious or cultural sensitivities we should be aware of?”

“As a Mayan I believe the world ended in 2012.”

I’m pretty sure the word ”smartass” is now a permanent part of my medical records.

My chest and stomach were then covered with stickers attached to wires that went to a machine that measured my breathing, heart rate, eye color, measurements, pet peeves, favorite television station, turn-ons, turn-offs–everything, in fact, except my blood pressure, which a nurse would have to come and check every four hours.

Since I was staying in a teaching hospital I was also visited by groups of approximately twenty-seven people in lab coats, all of whom politely asked if they could examine me, which meant hiking up my gown and acting like it was our third date. I haven’t been naked in the presence of so many people since high school gym class, but I didn’t complain. Unlike dodgeball I knew I had a good chance of beating this cancer, and Dr. Coldfinger and Co. were stepping up to be part of my team. I was going to make their job as easy as possible. Maybe I got a little too comfortable. Every time the door opened I hiked up my gown, only to have one person say, ”Whoops, wrong room!”

Apparently if you’ve seen one you’ve seen ‘em all doesn’t apply for certain regions.

I was also visited by a nice young doctor who asked me if I wanted to be listed as DNR–Do Not Resuscitate. The question set me back a bit. I was certain of my answer. If it was an option I wanted to be Do Resuscitate, Please! It was just the reality settling in. I hadn’t been in a hospital as a patient in thirty-nine years, when I was treated for a condition that, ironically, was a risk factor for the cancer I now had. I’d known I was going to end up in the hospital again eventually. I just didn’t expect to be facing questions of life and death quite so soon, or so suddenly.

That evening I was taken for a spin around the hospital by a nice orderly named Leonard. He was taking me for another ultrasound at eleven thirty at night, and I’m pretty sure he was taking me around the entire hospital just for fun.

In a strange and half-lit room I was gooped up and given another ultrasound in search of the deadly blood clot, which declined to make an appearance, then sent back to the closet for a shot of blood thinner, which the nurse assured me would be just like a mosquito bite. She meant one of those prehistoric mosquitoes, with a schnozz like an elephant. And then I managed to sleep, waking only to hike up my gown whenever the door opened, even though the nurses kept telling me they’d use my arm to take my blood pressure.

Later that evening I’d get up out of my hospital bed and go to the bathroom next door. For some reason the emergency room bathroom didn’t have a lock, so as I was sitting there trying to relieve myself the door opened. “Occupied!” I yelled. The doctor who’d opened the door was talking to someone–obviously his need wasn’t that urgent–so he didn’t hear me. He just stood there, one hand on the doorknob, with me exposed to the world. This would be the only time I’d have my gown hiked up that I felt genuinely embarrassed. Finally he turned around, said, “Oh!” and closed the door. I’ll never know who you were, doc, but thanks for the look-in.

In the morning I woke with heartburn, probably because I hadn’t eaten anything in nearly eighteen hours. I thought this meant I needed an antacid and maybe some breakfast. The staff thought it meant I needed an EKG, which meant adhering more wires to my chest. Two weeks later I’d still be washing off sticker residue.

“We dont want to alarm you, said the nurse, ”but you could be having a heart attack.”

The only thing I found alarming was that the way she put it could give me a heart attack. Fortunately it turned out that what I needed was an antacid and some breakfast. This was followed by another shot of blood thinner from a slightly smaller mosquito, and then I was told I was being scheduled for surgery. The original plan had been to perform a biopsy, but the doctors decided that since the source of the trouble was in an easily accessible spot between my legs they’d cut out the middleman–or rather the manufacturer.

Surgery meant being moved upstairs to a luxury suite the size of a double-wide trailer, complete with a private bathroom, shower, sitting area, refrigerator, and, right across the hall, a pantry stuffed with all kinds of snacks and drinks, from chocolate milk and sodas to yogurt, cheese, and crackers. And a nurse who was professional, courteous, efficient, and who, when she was done with all her tasks, sprawled at the end of my bed and told us how much she was looking forward to going home and having a beer with her country singer boyfriend. I would have loved a beer myself, but, almost as good was having someone come in and talk to me as a person rather than a patient.

Then she left. My wife left too. My wife had been the best source of comfort and stability I could have hoped for, and more. She had gone above and beyond necessity to take care of me, but I now I needed her to take care of herself. I needed her to take care of the dogs. And I needed to crank up Take The Skinheads Bowling by Camper Van Beethoven and dance around the room, which I can’t do in the presence of other people.

A week after my orchiectomy I would learn I had an embryonal some-kind-of-noma, with an excellent chance of being completely cured. And half of it was a yolk sac, which made it sound even more like an alien parasite. It was fitting. Whenever the subject of astrology came up a college friend of mine liked to say, ”I’m a Cancer, sign of the crab. I’m two diseases nobody wants.” This made me wonder what cancer had to do with crabs, so I looked it up. Ancient doctors found that tumors, when cut, spread sideways, like a crab. Cancer is of the body, but behaves like an invader.

The prognosis was in the future, though. Alone the night before my surgery I wandered down the hall to a spot the nurse had shown me earlier. My room had everything except a window to the outside. It had been twenty-four hours since Id seen the sky. I’d been wired up but disconnected from the world. At the end of the hall was a window that looks over a section of Twenty-First Avenue I knew well. I could see the bar where I knew someone was playing pool. I could see the coffee shop where I knew someone was eating red velvet cake and laughing with friends. I could just make out the indie theater where I knew someone had escaped into the silvery darkness of a movie. The avenue itself was an artery pulsing with red and white lights, people illuminating the future. I had been all of them. I was all of them. I don’t want to be the heroic survivor who inspires others. I simply want to live.

The darkness deepened over the world below, but the lights brightened. I wondered if, in the months to come, I would still be as brave as I felt, if I would keep my sense of humor. I knew things would get worse before they’d get better, but I knew they would get better. The first most crucial step was taken because my doctor had been on the ball.

Like this:

Like Loading...

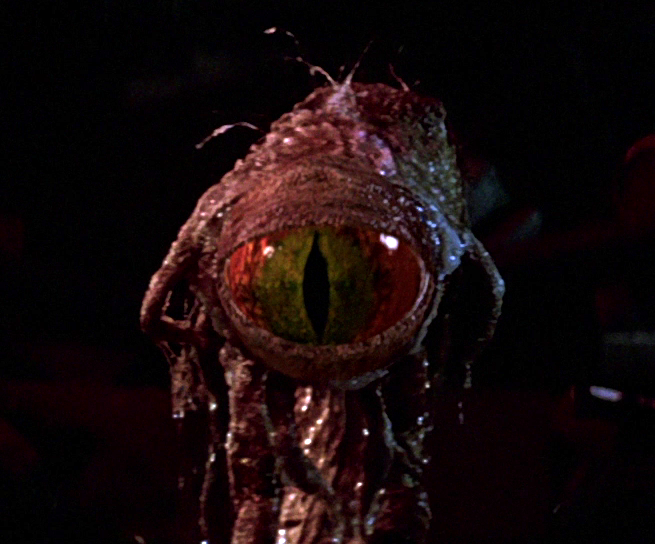

To address the detention area specifically, all staff have been very lax about sorting materials. Following the rebels’ escape through one of the trash compactors I was shocked to find that it contained not only broken storage containers and some droid parts. There was also at least one support beam that had been perfectly usable prior to their attempt to use it to stop the compacting process. I shouldn’t have to remind all staff that metals, resins, and other inorganic materials should be properly sorted into the appropriate color-coded disposal units on levels six and seven. The trash compactors on the detention level are strictly for organic waste: leftover food, former prisoners, etc. The dianoga I had captured and placed in the detention level trash system may seem like a ferocious animal, with its single eye and tentacles, but it is a sensitive aquatic creature. Its purpose is to facilitate the breakdown of organic waste. Its usefulness in this regard has made it cost-effective enough that we are still ahead financially in spite of the loss of seven Stormtroopers to unfortunate accidents. I don’t want to hear any more complaints about it.

To address the detention area specifically, all staff have been very lax about sorting materials. Following the rebels’ escape through one of the trash compactors I was shocked to find that it contained not only broken storage containers and some droid parts. There was also at least one support beam that had been perfectly usable prior to their attempt to use it to stop the compacting process. I shouldn’t have to remind all staff that metals, resins, and other inorganic materials should be properly sorted into the appropriate color-coded disposal units on levels six and seven. The trash compactors on the detention level are strictly for organic waste: leftover food, former prisoners, etc. The dianoga I had captured and placed in the detention level trash system may seem like a ferocious animal, with its single eye and tentacles, but it is a sensitive aquatic creature. Its purpose is to facilitate the breakdown of organic waste. Its usefulness in this regard has made it cost-effective enough that we are still ahead financially in spite of the loss of seven Stormtroopers to unfortunate accidents. I don’t want to hear any more complaints about it.