Source: Wikipedia

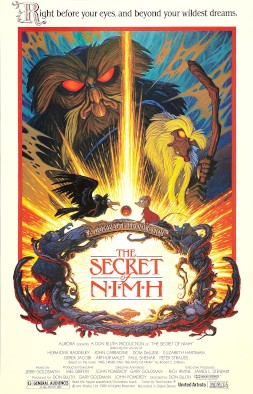

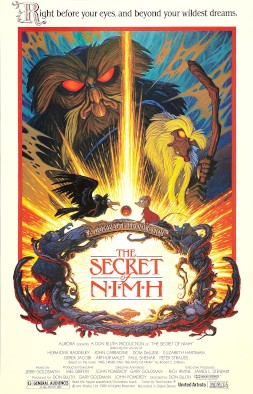

For some reason of all the films that made the summer of 1982 feel like on where I practically lived in movie theaters the one that’s stuck with me the most is The Secret Of NIMH, which came out in July of that year. I saw it twice that summer, which wasn’t unusual—this was before we had VCRs, and, in fact, just before the arrival of cable TV, and even after cable and VCRs became part of our lives I’d still frequently see a movie first with my parents or alone then go back with my friends. The second time I saw The Secret of NIMH was also a special free screening arranged by the local schools. Maybe this was because it was based on the Newbery Medal-winning novel by Robert C. O’Brien, Mrs. Frisby & The Rats Of NIMH.

I hadn’t read the book but my friend John, who went with me the second time, had, so I asked him what he thought of it.

“I hated it,” he said flatly.

I felt bad about this, as though I were somehow responsible. Yes, I thought it was a great movie and I told him how much I enjoyed it, but since it was free and every kid in my school packed the theater he probably would have gone anyway. I was so taken aback by his response I didn’t think to ask him why he hated it, but then I read the book, which I’d been meaning to do anyway, and I understood.

For the most part the book and movie tell the same story, although the name of Mrs. Frisby had to be changed to Brisby to avoid confusion with flying plastic discs: she’s a field mouse whose husband has been killed by the farmer’s cat. It’s early spring and she’s about to move her family to their summer home. The farmer plows over their winter home every spring, but her youngest son Timmy is sick from a spider bite and can’t be moved. With the help of a friendly crow named Jeremy she visits The Great Owl who tells her to go to the rats that live in the farm’s rosebush. When she does she learns her husband and the rats were the subject of experiments at the National Institute of Mental Health, or NIMH, that enhanced them physically and mentally. Her husband helped the rats escape and they’ve built an elaborate underground city, stealing electricity from the farm. Their husband continued helping the rats by drugging the farmer’s cat. She offers to do the same so the rats can come and move her home to a spot safe from the plow. She’s caught in the act by one of the farmer’s children and overhears that people from NIMH are coming to gas the farm’s rats. She escapes, the rats move her home, the rats, who were uncomfortable with stealing, set off to build an independent civilization, and Timmy gets better.

The movie was produced and directed by animator Don Bluth, who, along with fifty other animators, left Disney in 1979 in protest over declining animation quality. And The Secret Of NIMH really does have some excellent animation. Character movements are smooth, there are realistic-looking people and animals, there are water effects, lighting effects, and reflections. The color palette is broad and vivid. And they didn’t hold back making Mrs. Brisby’s meeting with The Great Owl, voiced by John Carradine, serious nightmare-fuel, or change the fact that in the story death is ever-present. This wasn’t a condescending kids’ show made to sell us fluffy toys.

Just a taste of the quality animation. Source: imgur

The problem is the movie tries to compress far too much into its 82-minute runtime. It doesn’t take much to understand why Mrs. Brisby wants to save her son, but in the book Timmy is more developed as a character. He’s clever and quiet, although also a storyteller who protects the younger mice, so he provides a contrast to his brother who’s strong and aggressive. The idea that intellect and imagination are just as valuable as strength, even in the hardscrabble world of a field mouse, gets lost in the movie where Timmy spends so much time sick in bed and has so few lines he might as well already be dead.

Then there’s the matter of the rats’ transformation in NIMH. In the book the rat leader Nicodemus tells Mrs. Frisby a lengthy story that could be a movie in itself of how they were captured, caged, and given injections, then taught to read. He tells her how they excelled but kept it a secret from their captors and how they eventually got to the farm’s rosebush. It’s almost Flowers For Algernon but from the mouse’s perspective. In the movie they’re given an injection and, in a trippy sequence, they’re magically transformed into sentient, literate super-rats.

In the book the rats’ lair has hallways and meeting rooms, but the film makes it strange, filled with multi-colored lights and twisting passageways. The unique look actually makes sense. Rats aren’t human so their civilization would look different. However Nicodemus, their leader, is changed from a rat like the others to a frail, raspy-voiced wizard who writes with glowing ink, makes objects levitate, and can summon up visions in a large ball by waving his staff.

The presence of magic in the film is the biggest divergence from the book, and it’s really what ruins the story. In the book the rats move Mrs. Frisby’s home with elaborate engineering. In the movie their apparatus is sabotaged by a conspiratorial rat named Jenner who also murders Nicodemus, Mrs. Brisby’s home sinks into the mud, there’s no explanation for how Timmy and the other children who are inside survive, and then Mrs. Brisby magically levitates her home with the help of a magical amulet Nicodemus gave her.

Bluth said he wanted to share his beliefs about the power of faith but this rewrite seemed more like an excuse to show off more elaborate effects and increase the drama of the ending.

I’m not opposed to remakes or even reboots, and plans for a new version of The Secret Of NIMH have floated around for years. It would possibly be redone as a miniseries, which makes sense—there’s too much story for even a long movie. There doesn’t seem to be much interest in actually doing it, though, and maybe that’s just as well. The book stands very well on its own, and while the movie has its weaknesses it also has equal strengths, including some necessary comic relief from Dom DeLuise as Jeremy the crow. For me there’s a certain amount of nostalgia attached to it but, watching it critically, as an adult, I can see the bad and good in it. I no longer love it. But I don’t hate it.

Like this:

Like Loading...

The James Webb Space Telescope is big in the news right now but, in a funny coincidence, we had something fall from the sky in our backyard recently. At first I didn’t know what it was and I saw it coming from a long way away, drifting up over the house like a mutant cloud, dark but with hints of light, trailing a narrow black tail.

The James Webb Space Telescope is big in the news right now but, in a funny coincidence, we had something fall from the sky in our backyard recently. At first I didn’t know what it was and I saw it coming from a long way away, drifting up over the house like a mutant cloud, dark but with hints of light, trailing a narrow black tail.

The

The